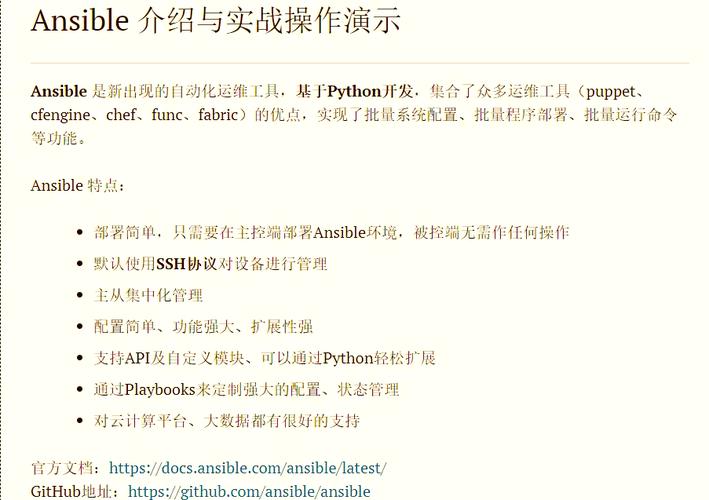

Of course! Using the Ansible API in Python is a powerful way to automate and integrate Ansible's capabilities directly into your applications, custom scripts, or CI/CD pipelines. It allows you to run playbooks, manage inventories, and control Ansible's execution programmatically.

Here’s a comprehensive guide covering the main ways to use the Ansible API, from the low-level ansible-runner to the high-level AnsibleInventory and AnsiblePlaybook APIs.

The Recommended Approach: ansible-runner

For most use cases, the ansible-runner project is the best choice. It's a standalone, lightweight tool and library designed specifically for running Ansible playbooks and other content programmatically. It handles the complexities of process execution, logging, and result parsing for you.

Why use ansible-runner?

- Decoupled: It doesn't require a full Ansible installation to be present in the Python environment.

- Isolated: It runs playbooks in a temporary, isolated directory, preventing side effects.

- Rich Output: It captures all output, including standard output, standard error, and the structured JSON results from Ansible.

- Simple API: The Python API is very straightforward.

Installation

First, install the ansible-runner package:

pip install ansible-runner

Basic Python Example: Running a Playbook

Let's create a simple playbook and then run it using the Python API.

Step 1: Create a sample Ansible project

mkdir my_ansible_project

cd my_ansible_project

# Create a simple playbook

cat > site.yml <<EOF

---

- name: Hello World Task

hosts: localhost

connection: local

tasks:

- name: Print a greeting

ansible.builtin.debug:

msg: "Hello from Ansible API!"

- name: Gather facts

ansible.builtin.setup:

gather_subset: min

EOF

# Create an inventory file (even for localhost)

cat > inventory <<EOF

localhost

EOF

# Create a requirements file for collections/roles if needed

touch requirements.yml

Step 2: Write the Python script

Create a Python script (e.g., run_playbook.py) in the same directory or elsewhere.

import ansible_runner

import pprint

# Define the path to your Ansible project directory

# The playbook path is relative to this project directory

project_dir = 'path/to/your/my_ansible_project' # <-- IMPORTANT: Change this to your actual path

playbook = 'site.yml'

print(f"Running Ansible playbook: {playbook}")

# Run the playbook

# The private_data_dir is where runner will store logs, artifacts, etc.

# It's good practice to make this unique for each run.

r = ansible_runner.run(

private_data_dir='./runner_output', # A directory for runner to use

project_dir=project_dir, # Your main Ansible project directory

playbook=playbook, # The playbook to run

inventory='inventory', # The inventory file to use

)

# Check the status of the run

print("\n--- Execution Status ---")

print(f"Status: {r.status}")

print(f"RC: {r.rc}") # Return code (0 for success, non-zero for failure)

# Print the stdout from the run

print("\n--- Standard Output ---")

print(r.stdout.read().decode('utf-8'))

# Print the detailed event results

print("\n--- Detailed Event Results ---")

for event in r.events:

if event['event'] == 'runner_on_ok':

pprint.pprint(event['event_data']['res']['results'])

# You can filter for other events like 'runner_on_failed', 'runner_on_skipped', etc.

# You can access the final fact cache

# print("\n--- Final Fact Cache ---")

# pprint.pprint(r.hostvars['localhost'])

Step 3: Run the script

python run_playbook.py

You will see the output from the playbook, and a runner_output directory will be created with detailed logs and artifacts.

The Low-Level Approach: ansible.executor

This approach uses Ansible's internal libraries directly. It's more complex because you have to manage Ansible's context (like loading plugins, preparing inventory, etc.) yourself. This is generally not recommended unless you are building a complex tool that needs deep integration with Ansible's core.

Warning: This API is considered internal and can change between Ansible versions. Use it with caution.

Example: Running a single Task

This example shows how to run a single ad-hoc task without a playbook.

from ansible.parsing.dataloader import DataLoader

from ansible.inventory.manager import InventoryManager

from ansible.vars.manager import VariableManager

from ansible.executor.task_queue_manager import TaskQueueManager

from ansible.playbook.play import Play

from ansible.plugins.callback import CallbackBase

import ansible.constants as C

# --- Setup Callback to capture results ---

class ResultCallback(CallbackBase):

def __init__(self, *args, **kwargs):

super(ResultCallback, self).__init__(*args, **kwargs)

self.host_ok = {}

self.host_unreachable = {}

self.host_failed = {}

def v2_runner_on_ok(self, result, **kwargs):

self.host_ok[result._host.get_name()] = result

print(f"TASK OK: {result.task_name} on {result._host}")

print(f"Result: {result._result}")

def v2_runner_on_unreachable(self, result, **kwargs):

self.host_unreachable[result._host.get_name()] = result

print(f"TASK UNREACHABLE: {result.task_name} on {result._host}")

def v2_runner_on_failed(self, result, **kwargs):

self.host_failed[result._host.get_name()] = result

print(f"TASK FAILED: {result.task_name} on {result._host}")

print(f"Result: {result._result}")

# --- Initialize Ansible context ---

# DataLoader loads YAML/JSON files

loader = DataLoader()

# InventoryManager loads the inventory

inventory = InventoryManager(loader=loader, sources='localhost,') # Use a comma-separated list or path to file

# VariableManager manages variables (from inventory, vars files, etc.)

variable_manager = VariableManager(loader=loader, inventory=inventory)

# --- Create a Play ---

# This is a simple play that runs on localhost

play_source = dict(

name="My API Play",

hosts='localhost',

gather_facts='no', # We'll skip gathering facts for simplicity

tasks=[

dict(action=dict(module='ansible.builtin.ping', ping_host='localhost'), register='ping_result'),

dict(action=dict(module='ansible.builtin.debug', msg='{{ ping_result }}')),

]

)

play = Play().load(play_source, variable_manager=variable_manager, loader=loader)

# --- Execute the Play ---

# Instantiate the callback

callback = ResultCallback()

# Create the TaskQueueManager

# The 'inventory' and 'variable_manager' are passed here

# 'stdout_callback' is used to print to console, our custom callback handles results

tqm = TaskQueueManager(

inventory=inventory,

variable_manager=variable_manager,

loader=loader,

passwords={}, # For sudo/su passwords if needed

stdout_callback=callback, # Optional: for console output

plugins=[]

)

try:

print("Executing play...")

tqm.run(play)

finally:

tqm.cleanup()

# --- Print final results ---

print("\n--- Final Results ---")

print("Hosts OK:", callback.host_ok.keys())

print("Hosts Unreachable:", callback.host_unreachable.keys())

print("Hosts Failed:", callback.host_failed.keys())

The High-Level Approach: AnsibleInventory and AnsiblePlaybook

These classes are part of the ansible.cli module and are designed to be used from the command line. While they can be used in Python, they are less flexible than ansible-runner and are tightly coupled to the CLI's argument parsing. This method is generally discouraged for programmatic use.

Summary: Which API to Choose?

| Method | Pros | Cons | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

ansible-runner |

Recommended. Decoupled, simple, robust, handles isolation and logging. | Requires a separate project directory structure. | 95% of use cases. Integrating Ansible into Python apps, CI/CD pipelines, and custom automation scripts. |

ansible.executor |

Full control over Ansible's execution. No project directory needed. | Complex. Internal API, can break. Requires manual setup of context. | Building deep, custom tools that need to embed Ansible's core logic directly. |

AnsiblePlaybook CLI |

Familiar if you use the CLI. | Tightly coupled to CLI arguments, less flexible, not designed for programmatic use. | Rarely. Maybe if you want to mimic a very specific CLI command exactly. |

For any new project, start with ansible-runner. It provides the cleanest, most maintainable, and most powerful way to interact with Ansible from Python.