Of course! Let's break down the try...finally block in Python, starting with a simple definition and then moving to detailed explanations, examples, and best practices.

The Core Idea

In Python, a try...finally block is used to define a block of code that you always want to execute, no matter what happens inside the try block. This is primarily used for cleanup actions, like closing a file, releasing a network resource, or unlocking a database, ensuring these actions happen even if an error occurs.

Basic Syntax

The structure is straightforward:

try:

# Code that might raise an exception

# ... (This is the "try" block)

finally:

# Code that will ALWAYS run

# ... (This is the "finally" block)

The finally block is optional, but if it's present, it will always execute, regardless of whether the try block:

- Runs to completion without any errors.

- Raises an exception that is not caught by an

exceptblock. - Raises an exception that is caught by an

exceptblock. - Uses a

return,break, orcontinuestatement.

Key Scenarios and Examples

Let's illustrate the "always runs" behavior with different scenarios.

Scenario 1: No Exception Occurs

If the code in the try block runs successfully, the finally block still executes right after.

print("Entering try block")

try:

print(" Inside try: No error here.")

x = 10

y = 20

print(f" Inside try: x + y = {x + y}")

finally:

print(" Inside finally: This always runs, even without an error.")

print("Exited try-finally block.")

Output:

Entering try block

Inside try: No error here.

Inside try: x + y = 30

Inside finally: This always runs, even without an error.

Exited try-finally block.Scenario 2: An Exception Occurs (and is NOT caught)

If an error occurs in the try block and there's no except block to handle it, the finally block runs before the exception propagates up and crashes the program.

print("Entering try block")

try:

print(" Inside try: About to cause a ZeroDivisionError.")

result = 10 / 0

print(" This line will never be reached.")

finally:

print(" Inside finally: Running even after an unhandled error!")

print("This line will also never be reached.")

Output:

Entering try block

Inside try: About to cause a ZeroDivisionError.

Inside finally: Running even after an unhandled error!

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 5, in <module>

ZeroDivisionError: division by zeroNotice how the finally block's message is printed before the error traceback is displayed. This proves it executed before the program terminated.

Scenario 3: An Exception Occurs (and IS caught)

This is where try...except...finally becomes very powerful. The finally block runs after the except block has finished its job.

print("Entering try block")

try:

print(" Inside try: About to cause a ValueError.")

int("hello")

except ValueError as e:

print(f" Inside except: Caught the error! {e}")

finally:

print(" Inside finally: Running after the exception was handled.")

print("Exited try-except-finally block successfully.")

Output:

Entering try block

Inside try: About to cause a ValueError.

Inside except: Caught the error! invalid literal for int() with base 10: 'hello'

Inside finally: Running after the exception was handled.

Exited try-except-finally block successfully.Scenario 4: The finally Block with a return Statement

This is a crucial and sometimes surprising rule: If a return statement is encountered in the try block, the finally block is executed before the function actually returns.

def my_function():

print("Entering my_function")

try:

print(" Inside try: About to return 10.")

return 10 # The return value is determined, but not yet sent back

finally:

print(" Inside finally: Running BEFORE the function returns.")

# Note: You can even override the return value here!

return 20 # This will be the *actual* return value

result = my_function()

print(f"The function returned: {result}")

Output:

Entering my_function

Inside try: About to return 10.

Inside finally: Running BEFORE the function returns.

The function returned: 20This behavior ensures that cleanup logic is not skipped, even when a function is designed to exit early via a return.

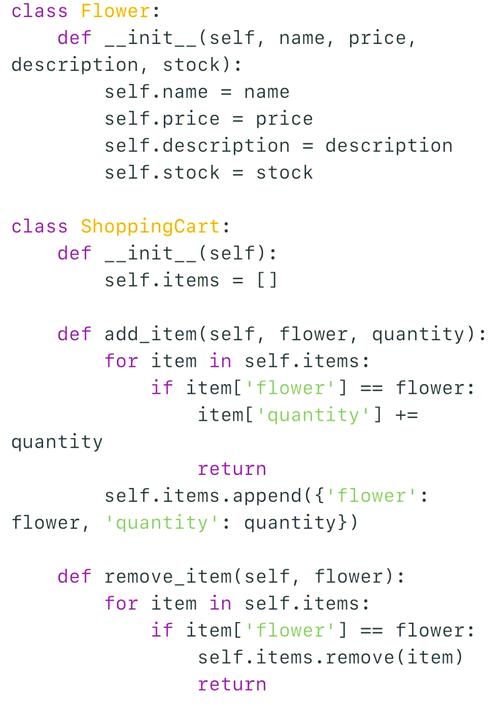

Common Use Cases

-

Resource Management (The Classic Example): This is the most important use case. You must always close files, database connections, and network sockets to free up system resources.

The WRONG way (without

finally):f = open("my_file.txt", "w") f.write("Hello, world!") # What if an error happens right here? # The program crashes, and f.close() is never called.The RIGHT way (with

finally):f = None try: f = open("my_file.txt", "w") f.write("Hello, world!") # An error could happen here, but finally will still run. except IOError as e: print(f"An error occurred: {e}") finally: if f: # Check if the file was opened successfully f.close() print("File has been closed.") -

Releasing Locks: In multi-threaded programming, you might acquire a lock. You must always release it, even if the code protected by the lock fails.

import threading lock = threading.Lock() def do_something(): try: lock.acquire() print("Lock acquired. Doing critical work...") # ... some code that might fail ... finally: lock.release() print("Lock released.") do_something()

The Modern Alternative: with Statements

For resource management like files, database connections, and locks, Python provides a more elegant and recommended syntax: the with statement.

The with statement automatically handles the setup and teardown of a resource, guaranteeing that its "exit" method is called, even if errors occur. This is functionally very similar to a try...finally block but is cleaner and less error-prone.

Example with with (for files):

# This is the preferred, modern way to handle files.

try:

with open("my_file.txt", "w") as f:

f.write("Hello, world!")

# If an error occurs here, the file 'f' is still automatically closed.

except IOError as e:

print(f"An error occurred: {e}")

# No need for a finally block to close the file!

The with statement calls special methods (__enter__ and __exit__) behind the scenes. The __exit__ method is equivalent to the code in your finally block.

Summary: try...finally vs. with

| Feature | try...finally |

with statement |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | General-purpose cleanup for any code block. | Specific for managing resources that have setup/teardown lifecycles. |

| Readability | Can be verbose. | Very clean and readable. |

| Safety | Safe, but relies on the programmer to remember the cleanup. | Safer; the cleanup is guaranteed by the language itself. |

| Use Case | Custom cleanup logic (e.g., resetting a global state, complex multi-step operations). | Files, database connections, locks, network sockets. |

Conclusion:

Use try...finally when you have a specific cleanup task that is not tied to a single, well-defined resource. For managing standard resources like files, always prefer the with statement as it is the more Pythonic, safer, and cleaner way to achieve the same goal.