Of course! Let's dive deep into wait() and notify() in Java. These are fundamental but often misunderstood methods for communication between threads.

The Core Idea: Why Do We Need Them?

Imagine a scenario where one thread (the Producer) is creating data and another thread (the Consumer) is processing that data. The Consumer can't process data if there isn't any, and the Producer shouldn't create more data if the buffer is full.

- Without

wait()/notify(), the Consumer might waste CPU cycles by constantly checking "is there data yet?" in a loop (this is called busy-waiting). - We need a way for the Consumer to go to sleep when there's no data and be woken up by the Producer when new data arrives.

wait() and notify() are the tools Java provides for this kind of efficient thread communication. They allow threads to pause and resume execution based on specific conditions, without consuming CPU resources.

Key Concepts and Rules

Before we see the code, you must understand these critical rules:

-

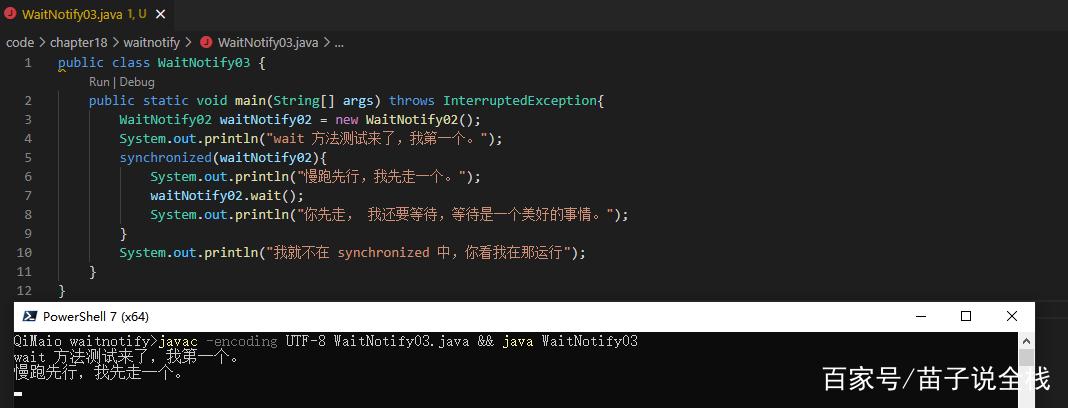

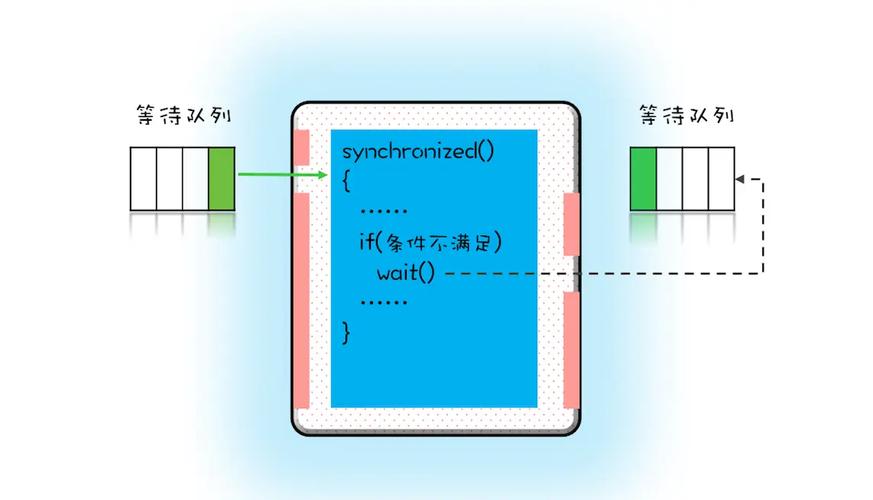

They Can Only Be Called Inside a Synchronized Block/Method: This is the most important rule.

wait()andnotify()are not instance methods you can call on any object. They must be called from within a context where the current thread holds the object's monitor lock (or intrinsic lock). This prevents race conditions. (图片来源网络,侵删)

(图片来源网络,侵删) -

The Purpose of

wait():- It tells the current thread to release the monitor lock and pause execution.

- The thread then enters the waiting set for that specific object.

- It will remain there until one of three things happens:

a. Another thread calls

notify()ornotifyAll()on the same object. b. Another thread callsinterrupt()on the waiting thread. c. It's "spuriously" awakened (rare, but you should always wait in a loop).

-

The Purpose of

notify():- It wakes up one single thread from the waiting set of the object.

- The awakened thread then attempts to re-acquire the monitor lock. It will block until it can get the lock.

- Crucially:

notify()does not release the lock immediately. The thread that callednotify()must release the lock (by exiting itssynchronizedblock) before the awakened thread can proceed.

-

The Purpose of

notifyAll():- It wakes up all threads waiting on the object's monitor.

- Just like

notify(), they will all compete to re-acquire the lock. Only one will succeed.

-

Always Wait in a Loop (The "Guarded Suspension" Pattern):

- Never call

wait()outside of awhileloop that checks the condition. - Why? A thread can be awakened for reasons other than

notify()(a "spurious wakeup"). The loop ensures that if the condition is still not met after waking up, the thread will simply callwait()again.

- Never call

The Classic Producer-Consumer Example

Let's build a simple thread-safe bounded buffer. The Buffer can hold only one item.

The Shared Buffer Class

This class will be accessed by both the Producer and Consumer threads.

public class Buffer {

private int item;

private boolean isEmpty = true; // Condition flag

// Called by the Producer to put an item in the buffer

public synchronized void put(int item) throws InterruptedException {

// Wait while the buffer is NOT empty

// The loop is crucial to handle spurious wakeups

while (!isEmpty) {

System.out.println("Producer: Buffer is full. Waiting...");

wait(); // Releases lock and waits

}

// If we get here, the buffer is empty. Produce the item.

this.item = item;

isEmpty = false;

System.out.println("Producer: Produced " + item);

// Wake up the Consumer thread

notify(); // Notifies the thread waiting on THIS object's monitor

}

// Called by the Consumer to get an item from the buffer

public synchronized int get() throws InterruptedException {

// Wait while the buffer IS empty

while (isEmpty) {

System.out.println("Consumer: Buffer is empty. Waiting...");

wait(); // Releases lock and waits

}

// If we get here, the buffer has data. Consume the item.

isEmpty = true;

System.out.println("Consumer: Consumed " + item);

// Wake up the Producer thread

notify(); // Notifies the thread waiting on THIS object's monitor

return this.item;

}

}

The Producer and Consumer Threads

public class Producer implements Runnable {

private final Buffer buffer;

public Producer(Buffer buffer) {

this.buffer = buffer;

}

@Override

public void run() {

for (int i = 1; i <= 5; i++) {

try {

buffer.put(i);

Thread.sleep(500); // Simulate production time

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

Thread.currentThread().interrupt();

}

}

}

}

public class Consumer implements Runnable {

private final Buffer buffer;

public Consumer(Buffer buffer) {

this.buffer = buffer;

}

@Override

public void run() {

for (int i = 1; i <= 5; i++) {

try {

buffer.get();

Thread.sleep(1000); // Simulate consumption time (slower)

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

Thread.currentThread().interrupt();

}

}

}

}

The Main Class to Run It

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Buffer buffer = new Buffer();

Thread producerThread = new Thread(new Producer(buffer));

Thread consumerThread = new Thread(new Consumer(buffer));

producerThread.start();

consumerThread.start();

try {

producerThread.join();

consumerThread.join();

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

System.out.println("Main: Program finished.");

}

}

Expected Output

Notice the alternating pattern. The Producer waits, then the Consumer waits, and they wake each other up.

Producer: Produced 1

Consumer: Consumed 1

Producer: Produced 2

Consumer: Consumed 2

Producer: Produced 3

Consumer: Consumed 3

Producer: Produced 4

Consumer: Consumed 4

Producer: Produced 5

Consumer: Consumed 5

Main: Program finished.wait() vs. sleep()

This is a very common point of confusion.

| Feature | wait() |

sleep() |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | For inter-thread communication. Pauses a thread until another thread signals it. | To pause a thread for a specific amount of time. |

| Locking | Releases the object's monitor lock. | Does not release any locks. |

| Location | Must be called inside a synchronized method or block. |

Can be called anywhere. |

| Wake-up | By notify(), notifyAll(), or timeout. |

By the expiration of the timeout. |

| Throws | IllegalMonitorStateException if not in a synchronized block. |

InterruptedException if interrupted. |

Modern Alternatives: java.util.concurrent

While wait() and notify() are essential to understand for interviews and low-level control, modern Java development favors the high-level concurrency utilities in java.util.concurrent. They are safer, easier to use, and less error-prone.

For the Producer-Consumer problem, the best modern tool is the BlockingQueue.

Example with BlockingQueue

import java.util.concurrent.ArrayBlockingQueue;

import java.util.concurrent.BlockingQueue;

public class ModernProducerConsumer {

public static void main(String[] args) {

// A thread-safe bounded buffer that can hold 1 item

BlockingQueue<Integer> queue = new ArrayBlockingQueue<>(1);

Thread producerThread = new Thread(() -> {

try {

for (int i = 1; i <= 5; i++) {

System.out.println("Producer: Trying to put " + i);

queue.put(i); // Blocks if the queue is full

System.out.println("Producer: Successfully put " + i);

Thread.sleep(500);

}

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

Thread.currentThread().interrupt();

}

});

Thread consumerThread = new Thread(() -> {

try {

for (int i = 1; i <= 5; i++) {

System.out.println("Consumer: Trying to get...");

Integer item = queue.take(); // Blocks if the queue is empty

System.out.println("Consumer: Successfully got " + item);

Thread.sleep(1000);

}

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

Thread.currentThread().interrupt();

}

});

producerThread.start();

consumerThread.start();

try {

producerThread.join();

consumerThread.join();

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

}

}

The BlockingQueue handles all the complex wait()/notify() logic internally, providing a clean and simple API (put() and take()). This is the recommended approach for most real-world applications.

Summary

| Method | What it Does | Key Points |

|---|---|---|

wait() |

Pauses the current thread and releases the lock. | Must be in a synchronized block. Always use in a while loop. |

notify() |

Wakes up one random thread waiting on the same object's monitor. | Does not release the lock. The notifying thread must exit the synchronized block first. |

notifyAll() |

Wakes up all threads waiting on the same object's monitor. | All awakened threads compete for the lock. Use when any waiting thread can proceed. |

sleep() |

Pauses the current thread for a set time. | Does not release any locks. |