Of course! Let's dive deep into wait() and notify() in Java. These are fundamental but often tricky methods for achieving thread synchronization.

The Core Problem: Why Do We Need wait() and notify()?

Imagine a classic producer-consumer scenario:

- A Producer thread adds items to a shared buffer.

- A Consumer thread removes items from the same shared buffer.

What if the buffer is empty? The consumer can't do anything. It shouldn't waste CPU cycles repeatedly checking if the buffer is full (this is called busy-waiting or "spinning"). It should be told to "wait" until an item is available.

What if the buffer is full? The producer can't add more items. It should wait until the consumer removes an item.

This is where wait() and notify() come in. They are the tools for inter-thread communication and efficient waiting.

The Golden Rules: wait() and notify() Must Be Used Inside a Synchronized Block

This is the most important rule. You cannot call wait() or notify() on an object unless the current thread has the object's intrinsic lock.

Why?

-

wait(): Releasing the lock is the whole point. When a thread callswait(), it:- Temporarily releases the lock on the object.

- Puts itself into a "waiting" state (on the object's wait set).

- Waits for another thread to notify it. This allows other threads to enter the synchronized block and modify the object's state.

-

notify(): Waking up a thread requires holding the lock. When a thread callsnotify(), it: (图片来源网络,侵删)

(图片来源网络,侵删)- Wakes up one (arbitrarily chosen) thread from the object's wait set.

- The woken thread will not run immediately. It must re-acquire the lock before it can continue execution from the point where it called

wait().

Method Breakdown

wait()

The wait() method tells the current thread to release the lock and wait until another thread calls notify() or notifyAll() on the same object.

There are three overloaded versions:

void wait(): Waits indefinitely until notified.void wait(long timeout): Waits for a specified amount of time (in milliseconds). If not notified, it will wake up after the timeout.void wait(long timeout, int nanos): Waits for a specified amount of time with nanosecond precision.

Key Behavior:

- It must be called from within a synchronized block or method.

- It releases the lock.

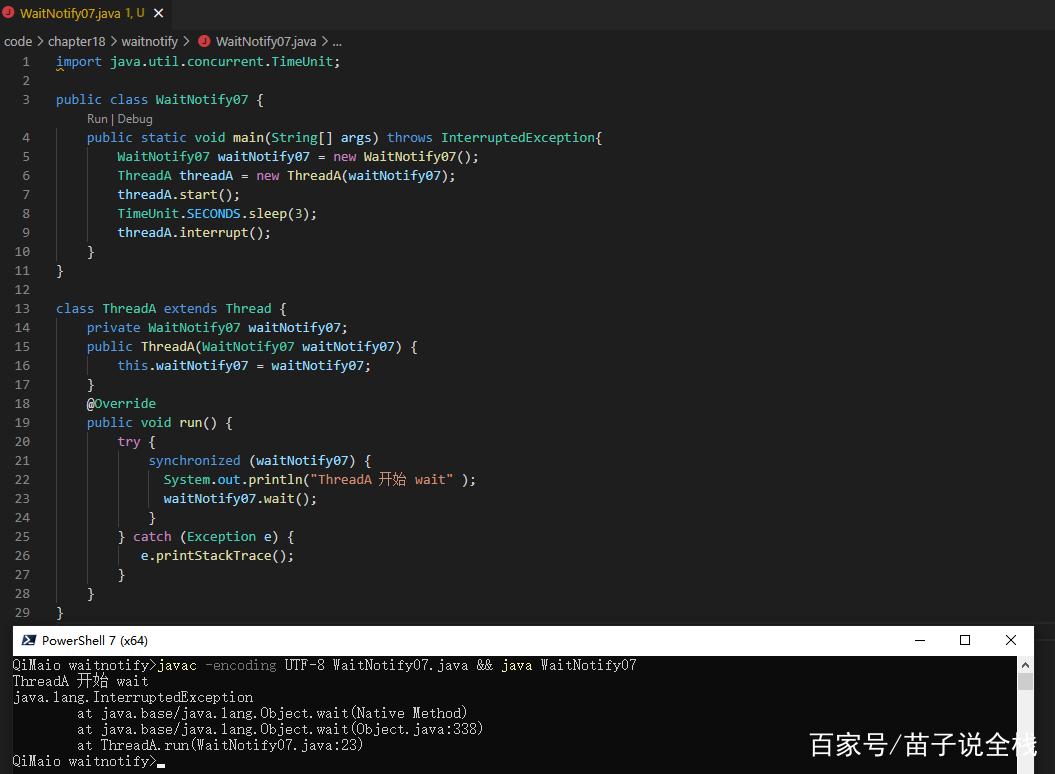

- It can throw

InterruptedExceptionif the thread is interrupted while waiting. You should handle this. - When it "wakes up," it re-acquires the lock before proceeding. This means other threads might have changed the object's state while you were waiting. You must always re-check the condition you were waiting for.

notify()

The notify() method wakes up one single thread that is currently waiting on the same object.

Key Behavior:

- It must be called from within a synchronized block or method.

- It does not release the lock immediately. The thread that called

notify()continues to hold the lock and will release it when it exits the synchronized block. - If multiple threads are waiting, which one gets woken up is not guaranteed (it's up to the JVM).

notifyAll()

The notifyAll() method wakes up all threads that are currently waiting on the same object.

Key Behavior:

- It must be called from within a synchronized block or method.

- All woken threads will try to re-acquire the lock. Only one will succeed, and the others will block again. This can lead to "thundering herd" problems, but it's often safer than

notify()as it prevents threads from being missed.

The Producer-Consumer Example (Classic Implementation)

This is the best way to understand how they work together.

The Shared Resource (Buffer)

public class SharedBuffer {

private final int[] buffer;

private int count = 0; // Number of items in the buffer

public SharedBuffer(int size) {

this.buffer = new int[size];

}

// Called by the Producer

public synchronized void put(int value) throws InterruptedException {

// Wait while the buffer is full

while (count == buffer.length) {

System.out.println("Producer: Buffer is full. Waiting...");

wait(); // Releases lock and waits

}

// This code is only reached when the buffer is not full

buffer[count] = value;

count++;

System.out.println("Producer: Produced " + value + ". Buffer count: " + count);

// Notify a waiting consumer that an item is available

notify(); // Wake up one consumer

}

// Called by the Consumer

public synchronized int get() throws InterruptedException {

// Wait while the buffer is empty

while (count == 0) {

System.out.println("Consumer: Buffer is empty. Waiting...");

wait(); // Releases lock and waits

}

// This code is only reached when the buffer is not empty

int value = buffer[count - 1];

count--;

System.out.println("Consumer: Consumed " + value + ". Buffer count: " + count);

// Notify a waiting producer that there is space

notify(); // Wake up one producer

return value;

}

}

The Producer and Consumer Threads

public class Producer implements Runnable {

private final SharedBuffer buffer;

public Producer(SharedBuffer buffer) {

this.buffer = buffer;

}

@Override

public void run() {

for (int i = 1; i <= 10; i++) {

try {

buffer.put(i);

Thread.sleep(100); // Simulate production time

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

Thread.currentThread().interrupt();

}

}

}

}

public class Consumer implements Runnable {

private final SharedBuffer buffer;

public Consumer(SharedBuffer buffer) {

this.buffer = buffer;

}

@Override

public void run() {

for (int i = 1; i <= 10; i++) {

try {

buffer.get();

Thread.sleep(200); // Simulate consumption time

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

Thread.currentThread().interrupt();

}

}

}

}

The Main Class to Run Everything

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

SharedBuffer buffer = new SharedBuffer(2); // A small buffer to see waiting in action

Thread producerThread = new Thread(new Producer(buffer));

Thread consumerThread = new Thread(new Consumer(buffer));

producerThread.start();

consumerThread.start();

try {

producerThread.join();

consumerThread.join();

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

System.out.println("Main: Simulation finished.");

}

}

Why the while loop is CRITICAL (Spurious Wakeups)

You might see if (condition) { wait(); } in some old examples. This is a bug.

The Java specification allows for "spurious wakeups," where a thread can wake up from wait() for no apparent reason. If you use an if statement, the thread might wake up, find the condition is still true, and proceed incorrectly, violating the lock's invariant.

The correct pattern is always a while loop:

// WRONG

synchronized (lock) {

if (!condition) {

lock.wait(); // Might wake up spuriously and proceed incorrectly

}

// ... proceed

}

// CORRECT

synchronized (lock) {

while (!condition) { // Re-check the condition after being woken up

lock.wait();

}

// ... proceed

}

Modern Alternatives: java.util.concurrent

While wait() and notify() are foundational, modern Java provides higher-level concurrency utilities that are safer, easier to use, and less error-prone. You should prefer these for new code.

-

BlockingQueue: This is the modern, go-to solution for the producer-consumer problem. It's a thread-safe queue that handles waiting and notifying internally.import java.util.concurrent.ArrayBlockingQueue; import java.util.concurrent.BlockingQueue; // Producer BlockingQueue<Integer> queue = new ArrayBlockingQueue<>(10); new Thread(() -> { try { for (int i = 0; i < 100; i++) { queue.put(i); // Blocks if the queue is full System.out.println("Produced " + i); } } catch (InterruptedException e) { /* ... */ } }).start(); // Consumer new Thread(() -> { try { while (true) { Integer item = queue.take(); // Blocks if the queue is empty System.out.println("Consumed " + item); } } catch (InterruptedException e) { /* ... */ } }).start(); -

java.util.concurrent.locks(Lock,Condition):Lockis a more flexible and powerful replacement forsynchronized.Conditionobjects are created from aLockand are the modern equivalent ofwait()/notify(). They allow you to have multiple "wait conditions" for a single lock.

import java.util.concurrent.locks.Condition; import java.util.concurrent.locks.Lock; import java.util.concurrent.locks.ReentrantLock; Lock lock = new ReentrantLock(); Condition notFull = lock.newCondition(); // Condition for "buffer is not full" Condition notEmpty = lock.newCondition(); // Condition for "buffer is not empty" // In producer: lock.lock(); try { while (isFull()) { notFull.await(); // Waits on the "notFull" condition } // ... produce item ... notEmpty.signal(); // Wakes up a consumer waiting on "notEmpty" } finally { lock.unlock(); }

Summary: wait()/notify() vs. Modern Alternatives

| Feature | wait() / notify() |

BlockingQueue / Lock / Condition |

|---|---|---|

| Complexity | Low-level, error-prone. | High-level, safer. |

| Ease of Use | Difficult to get right (spurious wakeups, missed signals). | Much easier and more intuitive. |

| Flexibility | One wait set per object. | Condition objects allow multiple wait sets. |

| Best For | Learning the fundamentals of concurrency. | Almost all production applications. |

| Performance | Can be very efficient when used correctly. | Generally excellent, with well-tuned algorithms. |