Of course! Let's break down notify() and wait() in Java. This is a fundamental concept for multi-threading, used for communication and synchronization between threads.

The Core Idea: A Producer-Consumer Analogy

Imagine a single plate of food (a shared resource) and two people: a Chef (Producer thread) and a Customer (Consumer thread).

- Chef's Job: Cook food and put it on the plate.

- Customer's Job: Eat the food from the plate.

This leads to two problems:

- Race Condition: What if the Customer tries to eat from an empty plate? Or the Chef tries to add food to a full plate?

- Inefficiency: What if the Customer is waiting for food? Instead of continuously asking "Is the food ready yet?" (busy-waiting, which wastes CPU), the Customer should just go to sleep. When the Chef puts the food on the plate, they should wake the Customer up.

wait(), notify(), and notifyAll() are Java's tools to solve this exact problem.

The Three Methods

These methods are not part of the Thread class. They are part of the Object class. This is a crucial point. Any object in Java can be used as a lock (or monitor), and any object can have threads waiting on it.

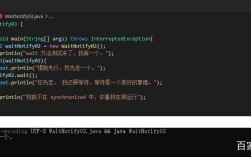

wait()

- What it does: Causes the current thread to pause execution and release the lock it holds on the object. The thread then goes into the "waiting" state.

- Why it's important: It allows a thread to give up the CPU without busy-waiting, making the application much more efficient.

- Key Rule:

wait()can only be called from within a synchronized block or method. If you call it outside, you'll get anIllegalMonitorStateException. - Variants:

wait(): Waits indefinitely until another thread callsnotify()ornotifyAll()on this object.wait(long timeout): Waits for a specified amount of time (in milliseconds). If it times out, it wakes up automatically.wait(long timeout, int nanos): More precise version with nanoseconds.

notify()

- What it does: Wakes up one single thread that is currently waiting on this object's monitor.

- Which thread? If multiple threads are waiting, Java chooses one arbitrarily (though it's often not truly random, it's up to the JVM). You cannot specify which thread to wake up.

- Important: The woken-up thread does not run immediately. It only moves from the "waiting" state to the "blocked" state, waiting to reacquire the lock. It will run only after the thread that called

notify()releases the lock. - Key Rule: Like

wait(),notify()can only be called from within a synchronized block or method.

notifyAll()

- What it does: Wakes up all threads that are currently waiting on this object's monitor.

- What happens next? Just like with

notify(), all the woken-up threads move to the "blocked" state. They will then compete to reacquire the lock. Only one will succeed and continue; the others will go back to waiting. - When to use it:

notifyAll()is generally safer thannotify(). It prevents a situation where a thread is woken up but finds the condition it was waiting for is still not met (this is called a "signal-to-wasting" problem).notifyAll()is often used when any waiting thread could proceed.

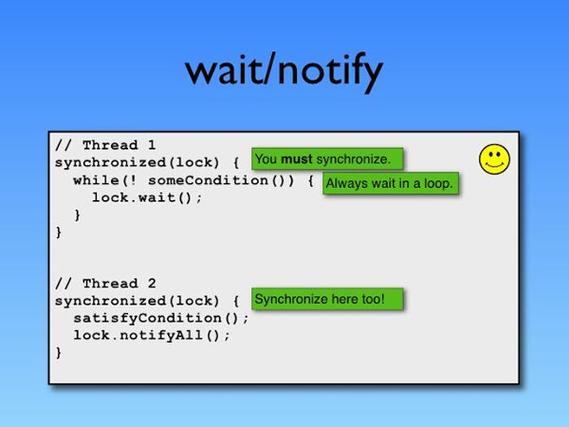

The Golden Rules (The Contract)

The use of wait() and notify() is governed by a strict contract:

-

Always use a

whileloop to check the condition, not anifstatement.- Why? A thread can be woken up for reasons other than

notify()(e.g., a spurious wakeup). When it wakes up, it must re-check the condition to see if it's actually safe to proceed. If you use anif, it might proceed even when the condition is false. - Correct Pattern:

synchronized (lockObject) { while (!conditionIsMet) { lockObject.wait(); // Release lock and wait } // Now it's safe to proceed }

- Why? A thread can be woken up for reasons other than

-

Always call

wait()andnotify()from within asynchronizedblock or method.- Why? This ensures that only one thread can manipulate the shared state or the waiting queue at a time. It establishes the "happens-before" relationship, guaranteeing that changes made by one thread are visible to another.

Code Example: The Classic Producer-Consumer

Let's model our Chef and Customer scenario.

The Shared Resource (The Plate)

This object will hold the food and be used for locking.

// Plate.java

public class Plate {

private String food;

private boolean isEmpty = true; // Our condition variable

// This is the "Consumer" action

public synchronized void get() throws InterruptedException {

// Use a while loop to check the condition

while (isEmpty) {

System.out.println("Customer: Plate is empty. Waiting...");

// Release the lock and wait for a notification

wait();

}

// If we get here, the plate is not empty

System.out.println("Customer: Eating the " + food);

this.food = null;

this.isEmpty = true;

}

// This is the "Producer" action

public synchronized void put(String food) throws InterruptedException {

// Use a while loop to check the condition

while (!isEmpty) {

System.out.println("Chef: Plate is full. Waiting...");

// Release the lock and wait

wait();

}

// If we get here, the plate is empty

System.out.println("Chef: Putting " + food + " on the plate.");

this.food = food;

this.isEmpty = false;

// Notify the waiting customer that food is ready

System.out.println("Chef: Notifying the customer.");

notify(); // or notifyAll();

}

}

The Threads (Chef and Customer)

// Chef.java

public class Chef extends Thread {

private final Plate plate;

public Chef(Plate plate) {

this.plate = plate;

}

@Override

public void run() {

try {

plate.put("Pizza");

Thread.sleep(2000); // Simulate cooking time

plate.put("Pasta");

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

}

}

// Customer.java

public class Customer extends Thread {

private final Plate plate;

public Customer(Plate plate) {

this.plate = plate;

}

@Override

public void run() {

try {

plate.get();

Thread.sleep(1000); // Simulate eating time

plate.get();

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

}

}

The Main Application

// ProducerConsumerDemo.java

public class ProducerConsumerDemo {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Plate plate = new Plate();

Chef chef = new Chef(plate);

Customer customer = new Customer(plate);

customer.start();

chef.start();

}

}

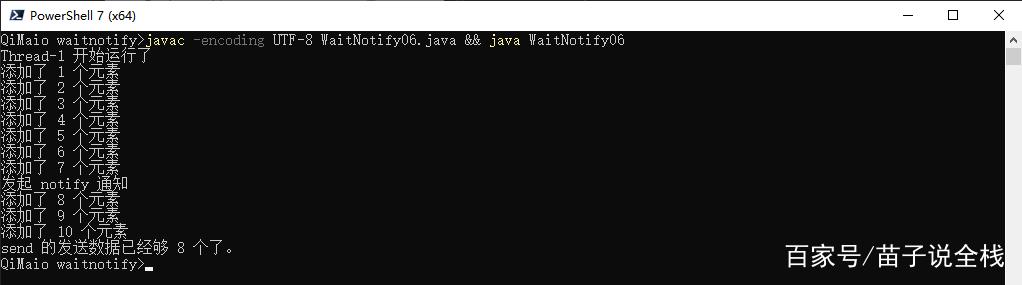

Expected Output

The output will be something like this, showing the interaction:

Customer: Plate is empty. Waiting...

Chef: Putting Pizza on the plate.

Chef: Notifying the customer.

Customer: Eating the Pizza

Chef: Plate is full. Waiting...

Customer: Plate is empty. Waiting...

Chef: Putting Pasta on the plate.

Chef: Notifying the customer.

Customer: Eating the PastaModern Alternatives

While wait() and notify() are foundational, modern Java provides higher-level concurrency utilities that are often safer and easier to use.

-

java.util.concurrent.locksPackage:ReentrantLock: A more flexible and powerful alternative tosynchronized. It has aConditionobject, which is like a more advanced version ofwait/notify. You can have multipleConditionobjects for different states, and you can specify which thread to wake up.Lock.lock()andCondition.await()/Condition.signal()are the modern equivalents.

-

java.util.concurrentPackage:- BlockingQueue (e.g.,

ArrayBlockingQueue,LinkedBlockingQueue): This is the recommended approach for most producer-consumer problems. It handles all the locking and waiting for you. You just put items into the queue and take them out. If the queue is full, aput()call will block. If it's empty, atake()call will block.

- BlockingQueue (e.g.,

Example with BlockingQueue:

import java.util.concurrent.ArrayBlockingQueue;

import java.util.concurrent.BlockingQueue;

public class ModernProducerConsumer {

public static void main(String[] args) {

BlockingQueue<String> queue = new ArrayBlockingQueue<>(1); // Plate with capacity for 1 item

// Producer

new Thread(() -> {

try {

System.out.println("Producer: Putting Pizza");

queue.put("Pizza");

Thread.sleep(2000);

System.out.println("Producer: Putting Pasta");

queue.put("Pasta");

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

}).start();

// Consumer

new Thread(() -> {

try {

System.out.println("Consumer: Waiting for food...");

String food1 = queue.take(); // Blocks if queue is empty

System.out.println("Consumer: Eating " + food1);

String food2 = queue.take(); // Blocks if queue is empty

System.out.println("Consumer: Eating " + food2);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

}).start();

}

}

Summary

| Feature | wait() / notify() |

Modern Alternatives (BlockingQueue, Lock) |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | Low-level, manual control over threads and locks. | High-level, abstracts away the complexity. |

| Safety | Prone to errors if not used correctly (e.g., spurious wakeups). | Much safer, handles edge cases internally. |

| Use Case | Good for learning and simple, custom synchronization needs. | Recommended for production code, especially producer-consumer patterns. |

| Complexity | High. You manage the condition and the lock. | Low. The framework manages the condition and the lock. |