Of course! Let's dive deep into Python's Tornado web framework. I'll cover what it is, why you'd use it, its core concepts, and a complete practical example.

What is Tornado?

Tornado is a Python web framework and asynchronous networking library. It was developed at FriendFeed and later open-sourced by Facebook before being donated to the Python Software Foundation.

The key thing that sets Tornado apart from most other Python web frameworks (like Django or Flask) is its asynchronous, non-blocking I/O nature.

The Big Idea: Asynchronous & Non-Blocking

To understand Tornado, you need to understand the difference between blocking and non-blocking I/O.

Traditional (Blocking) I/O (e.g., Flask with a WSGI server)

Imagine a coffee shop with one barista.

- A customer (a web request) comes in and orders a coffee.

- The barista (the server) starts making the coffee. While the coffee is brewing (a slow I/O operation like a database query or an API call), the barista does nothing else.

- The barista waits patiently for the coffee to be ready.

- Once ready, the barista gives the coffee to the customer and moves on to the next customer.

This is simple and works well for a small number of customers. But if 100 customers arrive at once, they will all have to wait in a long line, and most of the time, the barista is just idle, waiting for coffee to brew.

Tornado (Non-Blocking) I/O

Now, imagine a coffee shop with one very efficient barista who knows how to multitask.

- Customer A orders a coffee.

- The barista starts the coffee brewing.

- Instead of waiting, the barista immediately takes the order from Customer B.

- While both coffees are brewing, the barista takes the order from Customer C.

- As soon as Coffee A is ready, the barista finishes serving Customer A. Then, as soon as Coffee B is ready, they serve Customer B.

This barista is using non-blocking I/O. They are never idle waiting for a slow task. They just start a task and immediately move on to the next one, keeping track of which task needs to be completed next.

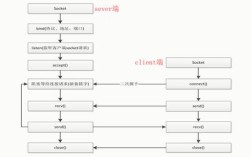

How does this translate to web servers?

- Blocking Server: Can only handle one request at a time per worker process. It waits for the entire request (including slow database/API calls) to finish before moving to the next one. This limits its ability to handle high concurrency.

- Tornado Server: Can handle thousands of concurrent connections. When it encounters a slow I/O operation (like a database query), it doesn't wait. It tells the database to "call me back when you're done" and immediately moves on to process other incoming requests. When the database responds, Tornado's callback function is executed to complete the original request.

Core Concepts of Tornado

Tornado's architecture is built around a few key concepts.

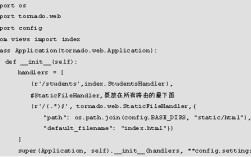

a. tornado.web.Application

This is the central object of your Tornado application. It's a collection of request handlers and the settings that go with them. You create a single Application instance at the start of your program.

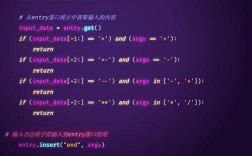

# app.py

import tornado.web

import tornado.ioloop

class MainHandler(tornado.web.RequestHandler):

def get(self):

self.write("Hello, Tornado World!")

# Create the application

app = tornado.web.Application([

(r"/", MainHandler), # URL mapping: regex -> Handler class

])

if __name__ == "__main__":

app.listen(8888)

tornado.ioloop.IOLoop.current().start()

b. tornado.web.RequestHandler

This is the heart of your application logic. You create a subclass of RequestHandler for each "page" or endpoint in your site. Tornado automatically calls the appropriate method (e.g., get(), post()) based on the HTTP request method.

Common methods you'll override:

get(self): Handles GET requests.post(self): Handles POST requests.write(self, chunk): Writes the given chunk to the output buffer.self.set_header(name, value): Sets an HTTP header.self.render(template_name, **kwargs): Renders a template with the given arguments.

c. The IOLoop (Input/Output Loop)

This is Tornado's event loop. It's the engine that drives the asynchronous operations. It listens for events (like a new network connection or a callback from a database) and executes the corresponding code.

You typically start it once with tornado.ioloop.IOLoop.current().start(), and it runs until you stop it.

d. Asynchronous Operations with async/await (Modern Tornado)

Modern Tornado (since version 5.0) fully embraces Python's async and await keywords. This makes writing asynchronous code much cleaner and more intuitive than the older callback style.

When you call an asynchronous function (one that is defined with async def), you await it. This await keyword tells the IOLoop, "This is going to take some time. Pause this function here, go handle other requests, and come back to this line when the asynchronous operation is finished."

Example of a blocking vs. non-blocking database call:

-

Blocking (Bad for a web server):

import time # This is a fake slow database call def slow_db_query(): time.sleep(5) # The entire server will be blocked for 5 seconds! return "Data from DB" class MainHandler(tornado.web.RequestHandler): def get(self): data = slow_db_query() self.write(data) -

Non-Blocking (Good for a web server):

import tornado.gen import time # This is a fake async slow database call async def async_slow_db_query(): # yield from a coroutine tells the IOLoop to pause this function await tornado.gen.sleep(5) # The server is NOT blocked. It can handle other requests. return "Data from DB" class MainHandler(tornado.web.RequestHandler): async def get(self): data = await async_slow_db_query() self.write(data)

Practical Example: A Simple Async "To-Do" List

This example will demonstrate:

- Creating an

Application. - Using

RequestHandlers. - Serving static files (CSS/JS).

- Using templates.

- Performing an asynchronous operation (simulated with

asyncio.sleep).

Project Structure

tornado_todo/

├── main.py

├── templates/

│ └── index.html

└── static/

├── style.css

└── app.jsStep 1: main.py (The Server)

This file sets up the Tornado application and its handlers.

# main.py

import tornado.web

import tornado.ioloop

import tornado.httpserver

import tornado.options

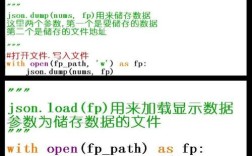

import json

import asyncio

from datetime import datetime

# Define command-line options

tornado.options.define("port", default=8888, help="run on the given port", type=int)

class MainHandler(tornado.web.RequestHandler):

"""Serves the main HTML page."""

def get(self):

# Render the index.html template

self.render("index.html")

class TodoAPIHandler(tornado.web.RequestHandler):

"""Handles API requests for the to-do list."""

# In a real app, this would be a database.

# We use a class variable to share state between requests.

todos = []

async def get(self):

"""Returns the list of all todos."""

# Simulate a slow database query

await asyncio.sleep(1) # Non-blocking wait!

self.set_header("Content-Type", "application/json")

self.write(json.dumps(TodoAPIHandler.todos))

async def post(self):

"""Adds a new todo to the list."""

# Simulate a slow database write

await asyncio.sleep(1.5) # Non-blocking wait!

data = tornado.escape.json_decode(self.request.body)

todo_text = data.get("text", "")

if not todo_text:

self.set_status(400)

self.write({"error": "Todo text cannot be empty"})

return

new_todo = {

"id": len(TodoAPIHandler.todos) + 1,

"text": todo_text,

"created_at": datetime.now().isoformat()

}

TodoAPIHandler.todos.append(new_todo)

self.set_status(201)

self.set_header("Content-Type", "application/json")

self.write(json.dumps(new_todo))

def make_app():

"""Creates and returns the Tornado application."""

return tornado.web.Application([

# Route for the main page

(r"/", MainHandler),

# Route for the API

(r"/api/todos", TodoAPIHandler),

# Route to serve static files (CSS, JS)

(r"/static/(.*)", tornado.web.StaticFileHandler, {"path": "static"}),

], template_path="templates")

if __name__ == "__main__":

tornado.options.parse_command_line()

app = make_app()

http_server = tornado.httpserver.HTTPServer(app)

http_server.listen(tornado.options.options.port)

print(f"Tornado server running on http://localhost:{tornado.options.options.port}")

tornado.ioloop.IOLoop.current().start()

Step 2: templates/index.html (The Frontend)

This is a simple HTML page with a form and a list. It includes links to our CSS and JS files.

<!-- templates/index.html -->

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8">Tornado To-Do List</title>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="/static/style.css">

</head>

<body>

<h1>Tornado Async To-Do List</h1>

<div class="container">

<form id="todo-form">

<input type="text" id="todo-input" placeholder="Add a new to-do..." required>

<button type="submit">Add</button>

</form>

<ul id="todo-list">

<!-- Todos will be added here by JavaScript -->

</ul>

</div>

<script src="/static/app.js"></script>

</body>

</html>

Step 3: static/style.css (Styling)

/* static/style.css */

body { font-family: sans-serif; background-color: #f4f4f4; }

.container { max-width: 600px; margin: 20px auto; padding: 20px; background: #fff; border-radius: 8px; box-shadow: 0 2px 4px rgba(0,0,0,0.1); }

#todo-form { display: flex; margin-bottom: 20px; }

#todo-input { flex-grow: 1; padding: 10px; border: 1px solid #ddd; border-radius: 4px; }

button { padding: 10px 15px; border: none; background-color: #007bff; color: white; border-radius: 4px; cursor: pointer; }

button:hover { background-color: #0056b3; }

#todo-list { list-style: none; padding: 0; }

#todo-list li { padding: 10px; border-bottom: 1px solid #eee; display: flex; justify-content: space-between; align-items: center; }

#todo-list li:last-child { border-bottom: none; }

.todo-text { flex-grow: 1; }

.delete-btn { color: red; cursor: pointer; background: none; border: none; font-size: 1.2em; }

Step 4: static/app.js (Client-Side Logic)

This JavaScript code fetches todos from our API and adds new ones using async/await on the client side as well.

// static/app.js

document.addEventListener('DOMContentLoaded', () => {

const todoForm = document.getElementById('todo-form');

const todoInput = document.getElementById('todo-input');

const todoList = document.getElementById('todo-list');

// Function to fetch and display all todos

async function fetchTodos() {

try {

const response = await fetch('/api/todos');

if (!response.ok) {

throw new Error('Failed to fetch todos');

}

const todos = await response.json();

todoList.innerHTML = ''; // Clear current list

todos.forEach(todo => {

addTodoToList(todo);

});

} catch (error) {

console.error('Error fetching todos:', error);

}

}

// Function to add a single todo item to the DOM

function addTodoToList(todo) {

const li = document.createElement('li');

li.innerHTML = `

<span class="todo-text">${todo.text}</span>

<button class="delete-btn" data-id="${todo.id}">×</button>

`;

todoList.appendChild(li);

}

// Function to add a new todo via the API

async function addTodo(text) {

try {

const response = await fetch('/api/todos', {

method: 'POST',

headers: {

'Content-Type': 'application/json',

},

body: JSON.stringify({ text: text }),

});

if (!response.ok) {

throw new Error('Failed to add todo');

}

const newTodo = await response.json();

addTodoToList(newTodo);

todoInput.value = ''; // Clear input field

} catch (error) {

console.error('Error adding todo:', error);

}

}

// Event listener for form submission

todoForm.addEventListener('submit', (e) => {

e.preventDefault();

const text = todoInput.value.trim();

if (text) {

addTodo(text);

}

});

// Event listener for delete buttons (using event delegation)

todoList.addEventListener('click', (e) => {

if (e.target.classList.contains('delete-btn')) {

const id = e.target.getAttribute('data-id');

console.log(`Delete todo with id: ${id}`); // Delete functionality not implemented in this example

}

});

// Initial load of todos

fetchTodos();

});

How to Run

- Make sure you have Tornado installed:

pip install tornado

- Navigate to the

tornado_tododirectory in your terminal. - Run the server:

python main.py

- Open your web browser and go to

http://localhost:8888.

You will see the to-do list. When you add a new item, you'll notice a slight delay (simulated by the await asyncio.sleep() calls), but the browser won't freeze, and you can interact with the page. If you open your browser's developer tools and look at the Network tab, you'll see the API calls being made. If you open two browser tabs, you can see that Tornado handles both requests concurrently without one blocking the other.

When to Use Tornado?

- Long-Polling and WebSockets: Tornado is excellent for applications that require persistent connections, like chat applications, real-time notifications, or live data dashboards.

- High-Concurrency Services: If you need a web server that can handle thousands of simultaneous connections efficiently (e.g., an API gateway, a game server backend), Tornado is a great choice.

- I/O-Bound Workloads: If your application's performance is limited by waiting for external resources (database calls, HTTP requests to other services), Tornado's non-blocking nature will give you a huge performance boost.

When to Use Something Else (like Django or Flask)?

- Content-Heavy Sites: For traditional websites, blogs, or e-commerce stores where the main task is rendering pages from a database, Django's "batteries-included" approach (ORM, admin panel, templating) is often faster to develop with.

- Simplicity and Rapid Prototyping: Flask is incredibly simple and lightweight. For a small API or a simple website, Flask can be up and running with less boilerplate code.

- CPU-Bound Workloads: If your application is doing heavy calculations (image processing, machine learning), the GIL (Global Interpreter Lock) in Python will be the bottleneck, not I/O. In this case, using a multi-process server with WSGI (like Gunicorn with Flask/Django) is often more effective than Tornado's single-process, multi-threaded model.