Of course! "Diving into Python 3" is an excellent way to learn. It implies moving beyond just syntax and understanding the language's philosophy, core features, and practical application.

Let's structure this dive into three parts:

- The Core Philosophy: What makes Python 3, Python?

- The Essential Deep Dive: A tour of the most important features you must know.

- The Practical Application: How to build real things with Python.

Part 1: The Core Philosophy (The Zen of Python)

Before writing any code, understand the guiding principles. Open a Python interpreter and type:

>>> import this

You'll see "The Zen of Python," a collection of 19 aphorisms that explain the language's design. The most famous ones are:

- Beautiful is better than ugly. Code should be readable and aesthetically pleasing.

- Explicit is better than implicit. Be clear. Don't rely on "magic" that's hard to understand.

- Simple is better than complex. Solve problems in the most straightforward way possible.

- Readability counts. Your code will be read by others (and your future self). Make it easy to read.

- There should be one-- and preferably only one --obvious way to do it. This is a key difference from Python 2, which often had multiple ways to accomplish the same task.

This philosophy is why Python is so beloved for its clean and maintainable code.

Part 2: The Essential Deep Dive (Key Features of Python 3)

This is where we get our hands dirty. We'll cover the non-negotiable features that define modern Python.

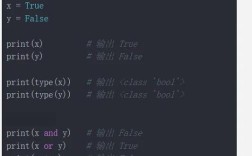

The print() Function (Not a Statement)

In Python 2, print was a statement. In Python 3, it's a function. This change is a perfect example of making Python more explicit and consistent.

- Python 2:

print "Hello, World" - Python 3:

print("Hello, World")

This makes it more flexible. You can now control the separator and the end character:

print("Hello", "World", sep="---", end="!\n")

# Output: Hello---World!

Integer Division is True Division

This is a huge and often-painful change for those coming from Python 2. In Python 2, dividing two integers would give you an integer (rounding down). In Python 3, it always gives you a float.

# Python 2 >>> 5 / 2 2 # Python 3 >>> 5 / 2 2.5 # If you want integer division (floor division) in Python 3, you use // >>> 5 // 2 2

This behavior is more intuitive and matches how mathematics works.

Unicode by Default

This is arguably the most important change in Python 3. In Python 2, there were two types: str (bytes) and unicode. This led to a constant headache of encoding and decoding.

In Python 3, there are two types: str (for Unicode text) and bytes (for raw 8-bit data). By default, all strings are Unicode.

# A string is Unicode by default

my_string = "Hello, 世界"

print(my_string)

# Output: Hello, 世界

# A bytes object is different

my_bytes = b"Hello"

print(my_bytes)

# Output: b'Hello'

# You encode a string to get bytes

encoded_bytes = my_string.encode('utf-8')

print(encoded_bytes)

# Output: b'Hello, \xe4\xb8\x96\xe7\x95\x8c'

# You decode bytes to get a string

decoded_string = encoded_bytes.decode('utf-8')

print(decoded_string)

# Output: Hello, 世界

This makes handling international text much simpler and less error-prone.

Powerful Iteration with for...in and range()

Python's for loops are designed to iterate over sequences. They are clean and expressive.

# Iterating over a list

fruits = ["apple", "banana", "cherry"]

for fruit in fruits:

print(fruit)

# Iterating over a string

for char in "Python":

print(char)

The range() function is also different. In Python 2, range() would generate a full list in memory, which could be inefficient for large numbers. In Python 3, range() returns a "range object" that generates numbers on the fly. It's memory-efficient and behaves like a sequence.

# This does NOT create a list of 1 billion numbers in memory.

# It creates an object that knows how to generate the next number.

for i in range(1000000000):

if i == 5:

print(f"Found it at: {i}")

break # We break early, so we never use much memory

Dictionary and Set Comprehensions

List comprehensions are a hallmark of Python. Python 3 added comprehensions for dictionaries and sets, making them just as powerful.

List Comprehension:

# Get the squares of even numbers from 0 to 9 squares = [x**2 for x in range(10) if x % 2 == 0] print(squares) # Output: [0, 4, 16, 36, 64]

Dictionary Comprehension:

# Create a dictionary where keys are numbers and values are their squares

squares_dict = {x: x**2 for x in range(5)}

print(squares_dict)

# Output: {0: 0, 1: 1, 2: 4, 3: 9, 4: 16}

Set Comprehension:

# Get unique lengths of words in a sentence

sentence = "the quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog"

unique_lengths = {len(word) for word in sentence.split()}

print(unique_lengths)

# Output: {2, 3, 4, 5}

Exception Handling with as

Python 3 refines exception handling. The except clause can now bind the exception instance to a variable using the as keyword.

try:

result = 10 / 0

except ZeroDivisionError as e:

print(f"An error occurred: {e}")

# Output: An error occurred: division by zero

This is cleaner than sys.exc_info() and gives you direct access to the exception object.

Advanced Data Structures: collections and dataclasses

Python's standard library is incredibly rich. For deep dives, you'll need to know these.

-

collections.Counter: A dictionary subclass for counting hashable objects. Perfect for frequency analysis.from collections import Counter words = ["apple", "banana", "apple", "orange", "banana", "apple"] word_counts = Counter(words) print(word_counts) # Output: Counter({'apple': 3, 'banana': 2, 'orange': 1}) print(word_counts.most_common(1)) # Get the most common item # Output: [('apple', 3)] -

collections.defaultdict: A dictionary that calls a factory function to supply missing values.from collections import defaultdict # Without defaultdict, you'd have to check for key existence # my_dict = {} # if 'key' not in my_dict: # my_dict['key'] = [] # my_dict['key'].append('value') # With defaultdict my_dd = defaultdict(list) my_dd['key'].append('value') # Works even if 'key' doesn't exist yet print(my_dd) # Output: defaultdict(<class 'list'>, {'key': ['value']}) -

dataclasses(Python 3.7+): A decorator that automatically adds special methods like__init__,__repr__, and__eq__to your classes. It saves you from writing boilerplate code.from dataclasses import dataclass @dataclass class Product: name: str price: float quantity: int = 0 # Optional field with a default # Python automatically creates the __init__ method! laptop = Product(name="Dell XPS", price=1200.50, quantity=10) print(laptop) # Output: Product(name='Dell XPS', price=1200.5, quantity=10)

Part 3: The Practical Application (How to Build Things)

Knowing the features is one thing; using them effectively is another.

Step 1: The Modern Workflow: Virtual Environments

Never, ever install packages globally. Use venv to create isolated environments for each project.

# Create a new environment named 'my_project_env' python -m venv my_project_env # Activate it (on macOS/Linux) source my_project_env/bin/activate # Activate it (on Windows) my_project_env\Scripts\activate # Now you're in the environment. Your prompt will change. # Install packages here pip install requests pandas # When you're done, deactivate deactivate

Step 2: Choose Your Tooling

- IDE (Integrated Development Environment):

- PyCharm: The gold standard. Excellent debugger, code completion, and project management.

- VS Code: A fantastic, lightweight, and free option with great Python extensions.

- Linter & Formatter: Essential for code quality.

black: The uncompromising code formatter. It formats your code for you, so you don't have to argue about style.flake8: A linter that checks for style errors and programmatic errors. Use it withblackfor a rock-solid codebase.

Step 3: The Project Structure

A simple, effective project structure for a small-to-medium project looks like this:

my_project/

├── my_project/ # The actual Python package

│ ├── __init__.py

│ ├── main.py # Your main application logic

│ └── utils.py # Helper functions

├── tests/ # Your test files

│ ├── test_main.py

│ └── test_utils.py

├── venv/ # Your virtual environment (add to .gitignore)

├── requirements.txt # Your project's dependencies

├── README.md # A description of your project

└── .gitignore # Files to ignore for version controlStep 4: A Mini-Project: Fetching and Processing Data

Let's use some of the features we've learned.

Goal: Fetch a list of "todos" from a public API, print the titles, and count how many are completed.

Setup

# Create a new project and environment mkdir todo_project cd todo_project python -m venv venv source venv/bin/activate pip install requests

Code (main.py)

import requests

from collections import Counter

def fetch_todos():

"""Fetches a list of todos from a public API."""

try:

response = requests.get("https://jsonplaceholder.typicode.com/todos")

response.raise_for_status() # Raises an exception for bad status codes (4xx or 5xx)

return response.json()

except requests.exceptions.RequestException as e:

print(f"Error fetching data: {e}")

return []

def main():

"""Main function to process and display todo data."""

todos = fetch_todos()

if not todos:

print("Could not retrieve todos.")

return

print("--- Todo Titles ---")

for todo in todos:

# Using an f-string for clean formatting

print(f"- {todo['title']}")

# Using a list comprehension to get a list of completion statuses

completed_statuses = [todo['completed'] for todo in todos]

# Using Counter to count the completed vs. not completed

status_counts = Counter(completed_statuses)

print("\n--- Summary ---")

print(f"Completed: {status_counts[True]}")

print(f"Not Completed: {status_counts[False]}")

if __name__ == "__main__":

# This block runs only when the script is executed directly

main()

Run it!

python main.py

This small project demonstrates:

- Importing libraries (

requests,Counter). - Error handling (

try...except). - Making an HTTP request.

- List comprehensions to extract data.

- Using

collections.Counterfor simple analysis. - f-strings for readable output.

- The

if __name__ == "__main__":guard, which is a standard Python practice.

Your Path Forward

You've now taken a deep dive into Python 3. The key to mastery is practice.

- Build Small Things: Don't try to build the next Facebook. Build a script that renames files in a folder, a simple web scraper, a tool to analyze a text file, a basic command-line game.

- Read Other People's Code: Go to GitHub and find open-source Python projects. See how they structure their code, handle errors, and use the standard library.

- Learn a Framework: Once you're comfortable with the core language, pick a framework and dive into web development (Django, Flask), data science (Pandas, NumPy), or automation (Selenium, Ansible).

Welcome to the wonderful world of Python 3! Enjoy the dive.