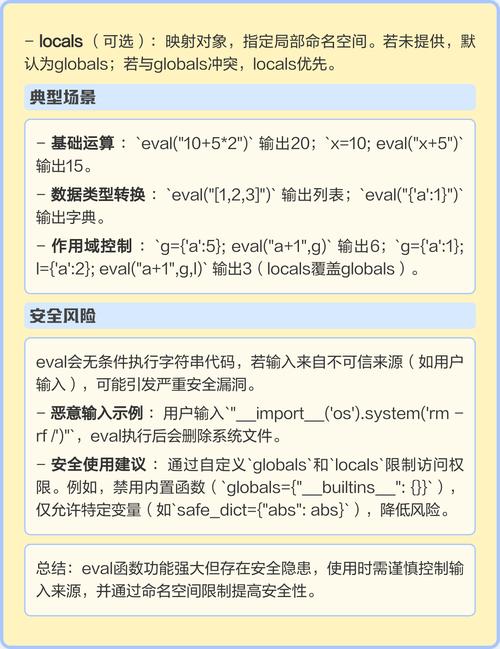

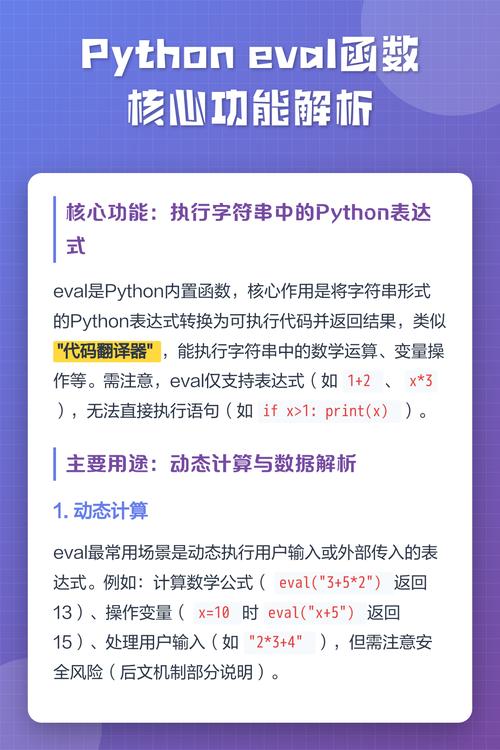

Of course. The eval() function in Python is a powerful but dangerous tool. When you use it, you can control the "environment" in which the code is executed by providing the locals() and globals() dictionaries.

Let's break down what this means, how it works, and the critical security implications.

The Short Answer: What eval(locals()) Does

When you call eval(expression, locals()), you are telling Python to evaluate the expression within a context that is only the current local variables and functions.

This has two main consequences:

- Isolation: It prevents the evaluated code from accessing global variables (like

open(),__import__(), etc.), which makes it significantly safer. - Control: It provides a clean, predictable "sandbox" for the

evaloperation.

The Detailed Breakdown

First, let's look at the eval() function's signature:

eval(expression, globals=None, locals=None)

expression: A string containing a valid Python expression or a compiled code object.globals: An optional dictionary that defines the global namespace for the evaluation. IfNone, the current global scope is used.locals: An optional dictionary that defines the local namespace for the evaluation. IfNone, the current local scope is used.

The Default Behavior (No locals)

If you don't provide the locals argument, eval uses the current local scope and the current global scope.

my_global_var = "I am global"

my_local_var = "I am local"

def test_eval_default():

# The expression can see BOTH global and local variables

result = eval("my_global_var + ' and ' + my_local_var")

print(f"Default eval result: {result}")

test_eval_default()

# Output: Default eval result: I am global and I am local

Using eval(locals())

Now, let's see what happens when we explicitly pass locals().

my_global_var = "I am global"

my_local_var = "I am local"

def test_eval_with_locals():

# The expression can ONLY see the local variables

result = eval("my_local_var", locals())

print(f"Eval with locals() result: {result}")

# This will raise a NameError because my_global_var is not in the local scope

try:

eval("my_global_var", locals())

except NameError as e:

print(f"Error as expected: {e}")

test_eval_with_locals()

# Output:

# Eval with locals() result: I am local

# Error as expected: name 'my_global_var' is not defined

Using eval(locals(), globals())

You can also provide both dictionaries. This gives you fine-grained control: you can specify a custom global scope and a custom local scope.

# Define some variables in our main script

main_x = 100

main_y = 200

# Define a custom global and local environment for eval

custom_globals = {"__builtins__": None} # Restrict built-ins

custom_locals = {"x": 10, "y": 20}

# The expression can only access the custom locals

# and has access to the custom globals (which is very restricted)

result = eval("x + y", custom_globals, custom_locals)

print(f"Custom scopes result: {result}")

# Output: Custom scopes result: 30

The Critical Security Implications of eval()

This is the most important part. NEVER use eval() on untrusted input.

The default behavior of eval() is extremely dangerous because it grants access to the entire Python environment, including powerful built-in functions.

The Danger of the Default eval()

Imagine a web application that lets a user input a mathematical formula.

# DANGEROUS CODE - DO NOT RUN ON UNTRUSTED INPUT

user_input = input("Enter a formula to calculate: ")

# This is vulnerable to Remote Code Execution (RCE)

# A malicious user could input: __import__('os').system('rm -rf /')

result = eval(user_input)

print(f"The result is: {result}")

A malicious user could enter a string like:

"__import__('os').system('echo pwned > /tmp/hacked.txt')"

This would execute arbitrary commands on your server, potentially deleting files or taking it over.

How eval(locals()) Improves Security

By using eval(locals()), you severely restrict the environment. The evaluated code cannot access global functions like __import__ or open.

# Much safer code

user_input = input("Enter a formula to calculate: ")

# Create a safe environment with only the allowed variables

safe_environment = {"a": 10, "b": 5}

try:

# The user can only use variables from safe_environment

result = eval(user_input, {}, safe_environment)

print(f"The result is: {result}")

except (NameError, SyntaxError) as e:

print(f"Invalid input: {e}")

# --- Test Cases ---

# 1. Safe input: "a + b * 2"

# Output: The result is: 20

# 2. Malicious input: "__import__('os').system('ls')"

# Output: Invalid input: name '__import__' is not defined

# The attack is thwarted!

# 3. Malicious input: "open('secret.txt', 'r').read()"

# Output: Invalid input: name 'open' is not defined

# The attack is thwarted!

Even better: For purely mathematical expressions, you can create an even more restricted environment by passing an empty dictionary for globals.

# The safest approach for math

math_globals = {"__builtins__": None} # Disables all built-in functions

math_locals = {"x": 100, "y": 50}

# This will fail on anything but simple math operations

# e.g., "x + y", "x / 10"

result = eval("x + y", math_globals, math_locals)

print(f"Math result: {result}")

Safer Alternatives to eval()

For most use cases, especially mathematical calculations, there are safer and more appropriate alternatives to eval().

ast.literal_eval()

This is the gold standard for safely evaluating strings containing Python literals (strings, numbers, tuples, lists, dicts, booleans, and None). It is explicitly designed to be safe and will not execute arbitrary code.

import ast

safe_string = "[1, 2, {'key': 'value'}]"

unsafe_string = "__import__('os').system('ls')"

# Works perfectly

print(ast.literal_eval(safe_string))

# Output: [1, 2, {'key': 'value'}]

# Raises a ValueError for unsafe code, which is what you want!

try:

ast.literal_eval(unsafe_string)

except ValueError as e:

print(f"Error: {e}")

# Output: Error: malformed node or string: <ast.Call object at ...>

Limitation: literal_eval cannot evaluate expressions like "1 + 2 * 3" or "foo.bar".

Custom Parser (for Math)

If you need to evaluate mathematical expressions, the best approach is to use a dedicated library like simpleeval.

pip install simpleeval

from simpleeval import simple_eval, InvalidExpression

expression = "x + y * 2"

variables = {"x": 10, "y": 5}

result = simple_eval(expression, names=variables)

print(f"SimpleEval result: {result}")

# Output: SimpleEval result: 20

# It will fail on any non-math syntax

try:

simple_eval("__import__('os')", names={})

except InvalidExpression:

print("Caught invalid expression!")

# Output: Caught invalid expression!

Summary

| Method | Use Case | Security | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

eval(expression) |

Evaluating arbitrary, trusted Python code. | EXTREMELY DANGEROUS. Avoid unless you control the input 100%. | AVOID for untrusted input. |

eval(expression, locals()) |

Evaluating code in a restricted local scope. | Safer. Prevents access to globals and built-ins. | Better, but still risky if the local scope is compromised. |

ast.literal_eval() |

Evaluating Python literals (strings, numbers, lists, etc.). | VERY SAFE. Designed for this purpose. | USE THIS if you only need to parse data structures. |

simple_eval() or similar |

Evaluating mathematical or custom expressions. | VERY SAFE. Parses only what you allow. | USE THIS for calculators or custom expression evaluation. |

Final Takeaway: Use eval(locals()) if you absolutely must eval and want to limit its scope. However, for 99% of cases, especially those involving user input, prefer ast.literal_eval() or a dedicated parsing library like simpleeval.