Of course! Let's dive deep into Python's nested scopes. This is a fundamental concept that underpins how Python resolves variable names, especially in functions and classes.

The Core Idea: The LEGB Rule

At its heart, Python's scoping rules are defined by the LEGB lookup order. When you use a variable, Python searches for it in this specific sequence:

- L - Local Scope: The innermost scope. This is the block of code inside the current function.

- E - Enclosing Scope(s): Any scopes that are "outside" the current function but still "inside" the outer function. This is what makes them nested.

- G - Global Scope: The module-level scope. This is the top-level scope of your

.pyfile. - B - Built-in Scope: The names built into Python, like

len(),print(),str, etc.

Python stops searching as soon as it finds the name in one of these scopes. If it doesn't find the name in any of them, a NameError is raised.

Nested Functions: The Classic Example

Nested functions are functions defined inside other functions. The inner function has access to variables from the outer (enclosing) function's scope.

Let's look at a simple example:

def outer_function(message):

# 'message' is in the Local scope of outer_function

message = "Hello from outer"

def inner_function():

# 'message' is NOT in the Local scope of inner_function.

# Python looks up and finds it in the Enclosing scope (outer_function).

print(message)

# Call the inner function

inner_function()

# Call the outer function

outer_function("This argument is ignored")

Output:

Hello from outerBreakdown:

outer_functionis called.- Inside

outer_function, the variablemessageis set to"Hello from outer". inner_functionis defined. It doesn't have its ownmessagevariable.- When

inner_function()is called, the lineprint(message)needs to findmessage. - L (Local):

inner_functionhas no localmessage. - E (Enclosing): Python finds

messagein the scope ofouter_function. It uses this value. - G (Global) / B (Built-in): The search stops here.

The nonlocal Keyword

What happens if you want to modify a variable from the enclosing scope, not just read it?

By default, if you try to assign to a variable in an inner function, Python will treat it as a new local variable for that function, even if a variable with the same name exists in the enclosing scope.

def counter_generator():

count = 0 # Variable in the enclosing scope

def increment():

# This line creates a NEW local variable 'count' inside 'increment'

# It does NOT modify the 'count' from the enclosing scope.

count = count + 1

print(f"Inner count: {count}")

increment()

print(f"Outer count: {count}") # The original 'count' is unchanged.

counter_generator()

Output:

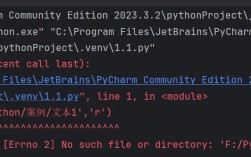

UnboundLocalError: local variable 'count' referenced before assignmentWait, why an error? Because Python sees count = count + 1 and decides count must be a local variable. But when it tries to read count on the right-hand side to assign it, it hasn't been created yet in the local scope. Hence the error.

This is where nonlocal comes in. The nonlocal keyword tells the inner function: "When you assign to this variable, don't create a new local one. Go up one level to the enclosing scope and modify the variable that's already there."

Corrected Example with nonlocal:

def counter_generator():

count = 0 # Variable in the enclosing scope

def increment():

# 'nonlocal' tells Python to use the 'count' from the enclosing scope.

nonlocal count

count = count + 1

print(f"Inner count: {count}")

increment()

print(f"Outer count: {count}") # Now the outer 'count' has been modified!

counter_generator()

Output:

Inner count: 1

Outer count: 1Now, increment() successfully modifies the count variable from counter_generator's scope.

The global Keyword

global works similarly to nonlocal, but it jumps to the Global (G) scope instead of the Enclosing (E) scope.

You use global to either:

- Read a global variable from inside a function.

- Modify a global variable from inside a function.

If you try to assign to a variable without global and there's no local or enclosing variable with that name, Python will automatically create a new local variable.

Example 1: Reading a Global Variable (works without global)

global_var = "I am global"

def read_global():

# Python finds 'global_var' in the Global scope.

print(global_var)

read_global()

Output:

I am globalExample 2: Modifying a Global Variable (requires global)

global_var = "I am global"

def modify_global():

# Without 'global', this would create a new local variable 'global_var'.

# The global 'global_var' would remain unchanged.

global global_var

global_var = "I have been modified!"

print(f"Before: {global_var}")

modify_global()

print(f"After: {global_var}")

Output:

Before: I am global

After: I have been modified!Summary Table: local, nonlocal, global

| Keyword | Scope it Affects | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| (None) | Local (default) | If you assign to a variable, it's created in the current function's local scope. If you only read it, Python searches up (LEGB). |

nonlocal |

Enclosing | Tells a function to use and modify a variable from an outer, but non-global function's scope. |

global |

Global | Tells a function to use and modify a variable from the module's top-level scope. |

Common Pitfalls and Best Practices

-

Read vs. Modify: Remember that reading a variable from an outer scope is automatic. Modifying it requires

nonlocalorglobal. -

Shadowing: Be careful not to accidentally "shadow" a variable from an outer scope by creating a local variable with the same name. This is a very common source of bugs.

x = 10 def my_func(): x = 5 # This is a NEW local 'x', it doesn't affect the global one. print(x) my_func() print(x) # Prints 10, not 5. -

Complexity: Deeply nested functions with lots of

nonlocalstatements can become hard to read and understand. If you find yourself needing this, consider if your code could be refactored into classes or a simpler structure. Classes provide a cleaner way to manage state withself.

Practical Use Case: Closures

Nested scopes are the foundation of closures. A closure is a function that "remembers" the environment in which it was created.

This is extremely powerful for creating function factories.

def make_multiplier(n):

"""This is a closure factory."""

def multiplier(x):

# 'n' is from the enclosing scope of make_multiplier.

# The inner function 'multiplier' 'closes over' 'n'.

return x * n

return multiplier

# Create two specific multiplier functions

times_3 = make_multiplier(3)

times_5 = make_multiplier(5)

print(times_3(10)) # Output: 30

print(times_5(10)) # Output: 50

Here, times_3 and times_5 are both closures. They carry with them the value of n (3 and 5, respectively) from the time they were created, even after make_multiplier has finished executing. This is a clean and efficient way to create specialized functions.